Using Artifacts to Inspire Critical Thinking

This article has been re-posted from the Smithsonian Center for Learning and Digital Access page. It was written by Mary Manning, College and Career Readiness Specialist, at Cleveland History Center of the Western Reserve Historical Society, a Smithsonian Affiliate in Ohio.

You don’t need to be a museum curator to use artifacts in a classroom. If you decide to use visual thinking strategies, which offer powerful ways to unravel all the symbolic power of artistic images, they may not seem to apply to artifacts, especially those used in daily life that may not carry symbolic meanings. However, artifacts are the most often forgotten yet most compelling kind of primary source—they may not tell us a story in words and figures, but they can lead us down trails of questions that can stimulate critical thinking and research in the classroom.

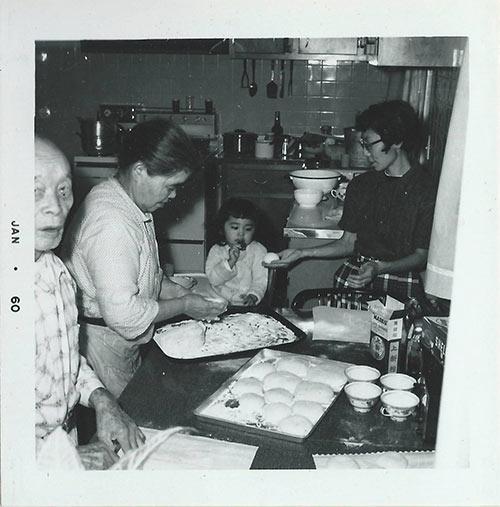

Sasaki Family Photograph, 1960.

Members of the Sasaki family are shown in their kitchen, preparing the actual cakes and treats that were made from the sticky mashed rice created in the mochi barrel. Cleveland History Center.

Making Sense of Mochi

When I began to design a Learning Lab collection that featured Asian Pacific American stories from the Cleveland History Center’s collections, I found one such compelling artifact—a mochi barrel used by the Sasakis, a Japanese-American family that lived in Cleveland, Ohio. At around two feet tall, our mochi barrel is a deceptively heavy contraption of wood curved around the cement dish inside. Inside the lid, a series of Japanese characters confirms that the barrel was made in Cleveland in 1947. I became fascinated by this object, so I began exploring its history through all the questions that it brought to my mind.

First, who was the Sasaki family? How did they come to Cleveland? I knew that much of Cleveland’s Japanese population arrived during World War II, and indeed, after being interned on the west coast, they were placed in Cleveland through the local War Relocation Authority office and efforts of local churches. Telling the story of the Sasakis and their mochi barrel meant combing through these local records, seeking references to the specific family or to situations that mirrored their experience. I also realized that I couldn’t explain how the barrel was used.

After some searching, I learned that making mochi could be a very intensive process, but one that has persisted through centuries of Japanese New Year celebrations. Telling the story of the mochi barrel then became about the process and science behind its function. The more I learned the more I saw these lines of questioning coming together: I wondered if their oppressive experience in internment camps made even more important to preserve cultural rituals like mochi making in their lives.

Questioning Through Artifacts

If you ever find one compelling object or image, don’t hesitate to bring it into your classroom, and use it to build out a lesson. Students are curious; when you let them observe an object for some time, and then ask what they see, they often respond with questions that cut to the core of why the object exists in the first place. They are often able to intuit the purpose of an unfamiliar object from what they already know. They can use their questions as a guide to research the historical context that fills in gaps of knowledge about the object and, potentially, creates more questions. In this process, there doesn’t always have to be just one story—strands of history inherently relate because they all tie back to that one original object.

Through this process, students seek a holistic view of an artifact or image, weighing information for value and bias and how it does or does not fit into the object’s story. There may be no bad questions, but there are certainly deeper questions that lead to higher-quality answers. By pushing students to question what they see through an intensive engagement with a single object, you hone a process of learning to interpret and draw meaning that enhances the way that students view the world around them. The Sasaki family and their mochi barrel provide the perfect example of why these skills serve students so well. The Sasakis do not play a role in any of the great triumphs and magnificent failures that would characterize a history of Cleveland in the twentieth century, but the ways in which they experienced internment and remade their lives tell us much about what is possible to find in between the events in our history books.

The Cleveland History Center is a Smithsonian Affiliate museum that collaborated on the Teacher Creativity Studio program. This program received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.