All Here: Accessibility and Diversity:Balancing Design, Content and Access in the Molina Family Latino Gallery

Many thanks to Eli Boldt, 2023 Smithsonian Leadership for Change intern, for this guest post. Boldt was one of several interns identifying and writing stories about underrepresented topics for Smithsonian Affiliations. This is one of two stories they completed this summer.

The Molina Family Latino Gallery, which opened in June 2022, is a precursor to the National Museum of the American Latino. The museum, legislated by Congress in 2020, is still in development and currently has exhibition space at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The Molina Gallery is a taste of what the museum will be: it represents the many varied histories of the Latino experience in America and the way Latino culture and figures have impacted and shaped the United States.

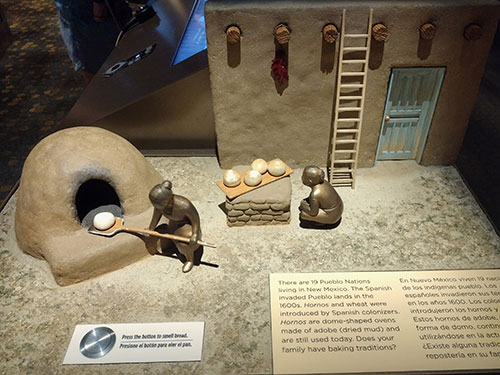

The exhibition was developed using a design model called I.P.O.P., a framework for building a content strategy focusing on Ideas, People, Objects, and Physical experiences. This allows the content to be diversified across the exhibition. Some people connect more with objects, while others connect with pictures and stories of people. Some people benefit heavily from having physical experiences, which tactile objects help to do.

Making an exhibit accessible is a balancing of the many types of people who are coming into the space. To design with accessibility in mind means finding the sweet spot where information is available and accessible to the most amount of people.

Under the direction of Elizabeth Ziebarth, Access Smithsonian helped bring the gallery’s vision for inclusive design to fruition. Leading a small but mighty team—Ziebarth is both director of Access Smithsonian and head diversity officer at the Smithsonian—the staff strives “for consistent and integrated inclusive design that provides meaningful access” in all their work. Ziebarth identifies making a space accessible to the blind as the most challenging.

“My rule of thumb is that if I can make something accessible to people who are blind or have low vision, I could probably make everything else accessible. The most challenging part of the design is to take something that is visual and make it into something that can deliver the content and the experience to somebody who can’t see it,” Ziebarth said.

Ways the gallery took on the challenge was creating a shoreline, a perimeter of cases around the middle. People who use canes can tap their way through and follow the path. There are cues and raised tabs on the ground to identify where QR codes, which pull up audio narration, are located. The gallery makes use of tactiles to tell the story as well. Tactiles are objects that are meant to be touched and interacted with. The museum shows a clay figurine and invites visitors to touch. There is a button that releases the smell of bread, another that plays the sounds of Domino Park, Miami, and releases the smell of coffee. There are audio descriptions and closed captions on video content for deaf and hard-of-hearing visitors, and space for wheelchair users to have as much mobility as possible.

The accessibility of the gallery is not unique, but it also is not the standard. It was made possible because accessibility was a part of the conversation from the start. Access Smithsonian was able to make a substantial impact on the exhibit’s layout, design, and technology because the designers and curators asked questions about accessibility all throughout.

“There’s no way that we can be everywhere, and we rely on developing relationships, trust, and a great understanding with teams,” said Ashley Grady, senior program specialist at Access Smithsonian. “They hopefully have the knowledge to make a lot of decisions independently, but they know that we’re always here for that guidance and access to user/expert testing or the disability community.”

The gallery was designed by Museum Environments, an organization that designs and creates multicultural and sustainable exhibits. Mariano Desmarás, the creative director for Museum Environments, was eager to help make the gallery accessible. He noted that as a consultant and designer, he can make suggestions but to do what the gallery ended up accomplishing, the backing of the institution and its leaders is essential. Desmarás points to his own background of having undiagnosed ADHD as a child and his experience with dyslexia, as well as his father’s later-in-life vision impairment, as reasons why accessibility is so important to him.

“Everybody had some sort of connection that they could make to why it would be important to have an inclusively designed exhibition space. And so that made a difference,” Ziebarth said.

That lived experience of seeing the struggles of people with disabilities is often a motivator for making spaces accessible; it is why user/expert testing was vital to the creation of the gallery and its accessible features.

The Institute for Human Centered Design (IHCD) is a non-profit organization doing work with inclusive design. Their user/experts are people who, through their own lived experiences, have expertise. IHCD and Access Smithsonian brought user/experts into the gallery as it was being built.

A typical user/expert testing session, as described by Grady, would begin with her meeting the exhibit team to understand what questions needed to be answered in that specific session. This ensured the right people were there to help. If they needed to test assistive listening devices, people who were Deaf or hard of hearing were prioritized.

“While those things can be intersectional, it’s important to make sure we’ve got the right people that would benefit the most from whatever the equipment is or element is,” Grady said.

The sessions were conversational. They engaged more with contextual inquiry to see how people engaged with the content. The sessions often included Access Smithsonian as well as people working on the exhibit’s content and design. This allowed for questions to be asked and answered as real people experienced the content.

The sessions lasted anywhere from 90 minutes to 2 hours, Grady explained, but they could look different depending on what was being tested and how many people were brought in. Sometimes only one or two components were being tested, whereas other times the sessions would be a comprehensive walkthrough of the gallery. Of course, user/expert testing was halted during the pandemic, but the team pivoted the testing to Zoom and continued their work.

Through user testing, things changed. Many were small changes, of course, but even small changes helped make every component as accessible as it could be. Color contrasts were changed, the heights of QR codes adjusted and font size perfected. When they got into the space, the design team mapped out the floorplan with blue tape according to ADA standards only to realize that the turn radius was not enough for motorized wheelchairs.

Michelle Cook, an inclusive design specialist with Access Smithsonian, stressed that the minimum standards are just that: the minimum.

“That’s one of the things that has been historically a challenge for those of us in the design field — and advocates for accessible or inclusive design — has been convincing people that it’s better to do more than the minimum because it serves a more diverse audience,” Cook said.

And diversity is what the Molina Family Latino Gallery is trying to communicate. To show that populations you might not think about are vital to the history of the United States. Latino history is American history: our cultures are intertwined. And within that diversity is the intersection of accessibility. They are two ideas that exist within each other.

“There’s this fear that inclusion focuses on a particular population and that it’s reductive,” Desmarás said. “I actually think that if it’s done right, inclusion is additive. That you’re saying that we’re all here.”

Source list:

- https://latino.si.edu/

The website for the National Museum of the American Latino, a project currently in production. At the end of 2020, Former President Trump signed a bill for its creation. What was formerly the Smithsonian Latino Center became the National Museum of the American Latino. - https://latino.si.edu/support/molina-family-latino-gallery

The website for the Molina Family Latino Gallery. The gallery is the precursor to the National Museum of the American Latino. - https://americanhistory.si.edu/

The website for the National Museum of American History, where the Molina Family Latino Gallery lives. - https://latino.si.edu/lead-donors-molina-family

The five children of Dr. C. David Molina collectively donated $10 million for the creation of the gallery. - https://access.si.edu/

The website for Access Smithsonian. This organization was created in 1991 and works with museums to create meaningful access for everyone. - https://museumenvironments.com/

Museum Environments is an organization that creates exhibits on large and small scales. They specialize in multicultural and bilingual exhibitions. For ¡Presente! they won the 2023 Smithsonian Award for Excellence in Exhibitions. - https://www.humancentereddesign.org/

The Institute for Human Centered Design is an education and design non-profit organization focused on universal, inclusive and accessible design. They were a part of creating the Molina Family Gallery, including but not limited to user/expert sessions. - https://www.humancentereddesign.org/user-expert-lab

User/experts have personal experience with disabilities or limitations and can provide expertise and advice for design. They were heavily involved in the creation of the Molina Family Latino Gallery. - https://www.ada.gov/law-and-regs/design-standards/

The website for the Americans with Disabilities Act and the design standards. As noted by Smithsonian employees through the experience of creating an accessible exhibition, ADA standards do not cover newer devices and are often insufficient. Described as the bare minimum.